“Until we have the courage to recognize cruelty for what it is -- whether its victim is human or animal -- we cannot expect things to be much better in this world. We cannot have peace among men whose hearts delight in killing any living creature. By every act that glorifies or even tolerates such moronic delight in killing, we set back the progress of humanity.” Thanks for your support For personal contact with me the founder please call 24/7 @ 442-251-6553 To all who have assisted in the past. Thank you. Your help is greatly appreciated. Peace and Joy.Founder Joseph F Barber

https://www.gofundme.com/URBAN-SURVIVAL-PACKS

https://www.gofundme.com/toolreplacementfund

https://the-family-assistants-campaign.blogspot.com/p/a-little-about-us.html

Never be afraid to raise your voice for honesty and truth and compassion against injustice and lying and greed. If people all over the world...would do this, it would change the earth.” Act now - Become A Supporting member of humanity to help end hunger and violence in our country

Since 2013, Veterans Project & The Family Assistance Campaign has provided free food assistance to more than 20,000 Veterans and their family members, distributing 445,000 lbs. of food. Feed Our Vets mission is to help Veterans in the United States, their spouses and children, whose circumstances have left them on the battlefield of hunger, and to involve the public in fighting Veteran hunger, through: (1) Community food pantries that provide regular, free food to Veterans and their families, (2) Distribution of related goods and services, (3) Public education and outreach.

Welcome to Truth, FREEDOM OR ANARCHY,Campaign of Conscience. , is an alternative media and news site that is dedicated to the truth, true journalism and the truth movement. The articles, ideas, quotes, books and movies are here to let everyone know the truth about our universe. The truth will set us free, it will enlighten, inspire, awaken and unite us. Armed with the truth united we stand, for peace, freedom, health and happiness for all

Pages

▼

Freedom of information pages

▼

Freedom Pages & understanding your rights

▼

Monday, October 30, 2017

WE THE PEOPLE IF WE CAN KEEP IT

EVENING FOLKS ITS Late AND I JUST GOT DONE WITH A 26 HRS DAY IF YOU WILL WORK HAS BEEN SHORT DO TO THE LOSS OF OUR TOOLS A MONTH BACK AND TO DATE NO ONE HAS BEEN ABLE TO RECOVER THEM FOR US BUT WHat we have found is the local law enforcement of the high desert seems to favor the law breakers over the law abiding citizens I have made a gofundme page to assist us in the recovery of our tools but to date we have had no contributions https://www.gofundme.com/toolreplacementfund

It could be that many of you fine people chose to believe that I personally have deceived you with the false allegations and statements made all around the net about me be a member of those that would still the honor of our fellow troops and veterans and in that you would be wrong i have proven to the department of defense allegations were false and that the veterans project and the family assistance campaign are 100% honest and true to we the people but then they had I was told already knew that but had to investigate the allegations do to the point of fact some people continued to make demands that we were being decebtive in our work and in the actions of our causes that to we have shown to be false and have been cleared of any and all actions ,in fact these actions will backfire on the two individuals responsible for their misrepresentation of the truth and the defamation of my character and filing false affidavits with the federal government I will also add that, I am very disappointed in Facebook as they even if in willingly assisted these individuals by allowing them to step aside of the same community standards we are all held to or punished for if we break these said rules and believe me they were informed of the se actions from day one and still allowed the defamation to continue. my advice from all this is simple this my friends Be honest with yourself and with people always do everything on time. Never give up, go to your goals, even if all the bad. In this life, all really, you only need to do. The more I talk to people, the more I am convinced that in general they have one goal - to become the richest dead in the cemetery,yet for me my goal differs from that A working class hero is something to be I think

It could be that many of you fine people chose to believe that I personally have deceived you with the false allegations and statements made all around the net about me be a member of those that would still the honor of our fellow troops and veterans and in that you would be wrong i have proven to the department of defense allegations were false and that the veterans project and the family assistance campaign are 100% honest and true to we the people but then they had I was told already knew that but had to investigate the allegations do to the point of fact some people continued to make demands that we were being decebtive in our work and in the actions of our causes that to we have shown to be false and have been cleared of any and all actions ,in fact these actions will backfire on the two individuals responsible for their misrepresentation of the truth and the defamation of my character and filing false affidavits with the federal government I will also add that, I am very disappointed in Facebook as they even if in willingly assisted these individuals by allowing them to step aside of the same community standards we are all held to or punished for if we break these said rules and believe me they were informed of the se actions from day one and still allowed the defamation to continue. my advice from all this is simple this my friends Be honest with yourself and with people always do everything on time. Never give up, go to your goals, even if all the bad. In this life, all really, you only need to do. The more I talk to people, the more I am convinced that in general they have one goal - to become the richest dead in the cemetery,yet for me my goal differs from that A working class hero is something to be I think

I have not always been a good man i have had my days in my youth i stepped outside the bounds of common folks did things that even to me today I find unacceptable but I have at the least tried to become a better man through the years by using my faith and honesty and to give of myself to others as much as i have been able to and the tools that were taken was a tool i used not only for my own well being but for that of those I was able to help with the money I could make with them and those that I could give work to

I am know working some with a friend of mine he needed my help and called me I came to his aid he tells me he is grateful but I am the truly grateful one if not for him we me and my family would have been on the streets just like many of those we have help through the years and understand not because we have been irresponsible or dishonest or been caught doing the wrong thing in any way but by the actions of those who have jealousy and hatred with in them and as it was said to my by them both because they could.

We're creating a positive information network. We need your help. https://www.gofundme.com/toolreplacementfund

The war on terror, economic disasters, racial wars, big pharma and food quality/modification. When you look at our world today you have to wonder how we got here.

It was in my later years of high school that I began to feel relief about something that bothered me for a long time: I started to realize how the world really works. Now at 55 years old, I’ve interviewed, met with and worked with many of the top researchers in the field of truth seeking and several conclusions are clear, but one more than others: our world is run by psychopaths.

I want to be very clear here, this is not meant to be a judgment, to rile up our emotions and call these people evil, no. This is about coming to a stark realization about what’s really going on in our world so that we can actually change it.

“As difficult as it was for me, I’ve come to an inescapable and profoundly disturbing conclusion. I believe that an elite group of people and the corporations they run have gained control over not just our energy, food supply, education, and healthcare, but over virtually every aspect of our lives; and they do it by controlling the world of finance. Not by creating more value, but by actually controlling the source of money.”

Why It’s Important

You know it, you feel it. Something is not quite right with our world and as each day goes by, more and more people are realizing this in a big way. In 2016 we witnessed millions begin to realize how elections are rigged and that we truly have no choice.

We began to learn on a wider level that our world leaders are closely involved with companies who fund terror and that the war on terror is fabricated to justify certain actions.

Coming to understandings like this shows a shift in our overall consciousness as a planet and helps us to realize how we can move forward. Should we keep voting expecting to see change when that’s not how our world actually works? Should we spend money supporting companies who are harming us and our environment? Should we support the medical system blindly vs working to create better health and wellness so illness doesn’t happen?

The more we understand how the game works, the more we know how to change it. Think of it this way, imagine you are playing a game and you find out someone is cheating and rigging the rules so you can never win. You may get up and just walk away and say I’m not playing anymore. Since that person can’t play with no one, they just stop. In a sense this is exactly what we need to work towards.

A transformation in consciousness comes from understanding, which leads to taking new actions, which helps to create a different world and bring solutions. But it starts with knowledge and consciousness.

EVOLVE

‘Imagine all the people living life in peace. You may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one. I hope someday you’ll join us, and the world will be as one.‘

‘You don’t need anybody to tell you who you are or what you are. You are what you are!’

‘My role in society, or any dreamers role, is to try and express what we all feel. Not to tell people how to feel. Not as a preacher, not as a leader, but as a reflection of us all. ‘

I hope I have expressed my heart here tonight and hope you will consider a contribution to our project

Get Behind Veterans Project & The Family Assistance Campaign Remember, Veterans Project & The Family Assistance Campaign is independent because it is wholly funded by YOU Veterans Project & The Family Assistance Campaign is one of the webs only truly independent sources of news and opinion. Without YOUR help it can not continue to exist. Please help - Act now! Click the link below Please provide whatever you can- $1, $5, $10, $20, $50, $100- To Use your debit/credit card or check pay here on facebook pay to Founder Joseph F Barber : WE believe that to meet the challenges of our times, human beings will have to develop a greater sense of universal responsibility. Each of us must learn to work not just for one self, one's own family or one's nation, but for the benefit of all humankind. Universal responsibility is the key to human survival. It is the best foundation for world peace Low income readers: DON'T send money, just encourage others to subscribe.

Thanks for your support For personal contact with me the founder please call 24/7 @ 442-251-6553 To all who have assisted in the past. Thank you. Your help is greatly appreciated. Peace and Joy.Founder Joseph F Barber

Thanks for your support For personal contact with me the founder please call 24/7 @ 442-251-6553 To all who have assisted in the past. Thank you. Your help is greatly appreciated. Peace and Joy.Founder Joseph F Barber

Never be afraid to raise your voice for honesty and truth and compassion against injustice and lying and greed. If people all over the world...would do this, it would change the earth.” Act now - Become A Supporting member of humanity to help end hunger and violence in our country

Since 2013, Veterans Project & The Family Assistance Campaign has provided free food assistance to more than 20,000 Veterans and their family members, distributing 445,000 lbs. of food. Feed Our Vets mission is to help Veterans in the United States, their spouses and children, whose circumstances have left them on the battlefield of hunger, and to involve the public in fighting Veteran hunger, through: (1) Community food pantries that provide regular, free food to Veterans and their families, (2) Distribution of related goods and services, (3) Public education and outreach.

JOSEPH F BARBER

JOSEPH F BARBER

Why Are All Those Racists So Terrified?

Why Are All Those Racists So Terrified?

Racism is not a new phenomenon and while it is an ongoing daily reality for vast numbers of people, it also often bursts from the shadows to remind us that just because we can keep ignoring the endless sequence of ‘minor’ racist incidents, racism has not gone away despite supposedly significant efforts to eliminate it. I say ‘supposedly’ because these past efforts, whatever personnel, resources and strategies have been devoted to them, have done nothing to address the underlying cause of racism and so their impact must be superficial and temporary. As the record demonstrates.

Racism is not a new phenomenon and while it is an ongoing daily reality for vast numbers of people, it also often bursts from the shadows to remind us that just because we can keep ignoring the endless sequence of ‘minor’ racist incidents, racism has not gone away despite supposedly significant efforts to eliminate it. I say ‘supposedly’ because these past efforts, whatever personnel, resources and strategies have been devoted to them, have done nothing to address the underlying cause of racism and so their impact must be superficial and temporary. As the record demonstrates.

I say this not to denounce the effort made and, in limited contexts, the progress achieved, but if we want to eliminate racism, rather than confine it to the shadows for it to burst out periodically, then we must have the courage to understand what drives racism and design responses that address this cause.

Otherwise, all of the best ideas in the world can do no more than repeat past efforts at dialogue, education, nonviolent action and the implementation of legislation designed to protect civil rights or even outlaw violence, which doesn’t work, of course, as the pervasive violence in our society demonstrates and was again graphically illustrated by the recent outbreak of ‘white nationalist’ violence in Charlottesville in the United States.

Racism directed against indigenous peoples and people of color has been a significant factor driving key aspects of domestic politics and foreign policy in many countries for centuries. This outcome is inevitable given the psychological imperatives that drive racist violence.

Racism – fear of, and hatred for, those of another race coupled with the beliefs that the other race is inferior and should be dominated (by your race) – is now highly visible among European populations impacted by refugee flows from the Middle East and North Africa. In addition, racism is ongoingly and highly evident among sectors of the US population but also in countries like South Africa as well as Australia and throughout Central and South America where indigenous populations are particularly impacted. But racism is a problem in many other countries too.

So why is fear and hatred of those of a different race so prominent? Let me start at the beginning.

Human socialization is essentially a process of terrorizing children into ‘thinking’ and doing what the adults around them want (irrespective of the functionality of this thought and behavior in evolutionary terms). Hence, the attitudes, beliefs, values and behaviors that most humans exhibit are driven by fear and the self-hatred that accompanies this fear. For a comprehensive explanation of this point, see ‘Why Violence?’ and ‘Fearless Psychology and Fearful Psychology: Principles and Practice’.

However, because this fear and self-hatred are so unpleasant to feel consciously, most people suppress these feelings below conscious awareness and then (unconsciously) project them onto ‘legitimized’ victims (that is, those people ‘approved’ for victimization by their parents and/or society generally). In short: the fear and self-hatred are projected as fear of, and hatred for, particular social groups (whether people of another gender, nation, race, religion or class).

This all happens because virtually all adults are (unconsciously) terrified and self-hating, so they unconsciously terrorize children into accepting the attitudes, beliefs, values and behaviors that make the adults feel safe. A child who thinks and acts differently is frightening and is not allowed to flourish.

Once the child has been so terrorized however, they will respond to their fear and self-hatred with diminishing adult stimulus. What is important, emotionally speaking, is that the fear and self-hatred have an outlet so that they can be released and acted upon. And because parents do not allow their child to feel and express their fear and hatred in relation to the parents themselves (who, fundamentally, just want obedience without comprehending that obedience is rooted in fear and generates enormous self-hatred because it denies the individual’s Self-will), the child is left with no alternative but to project their fear and hatred in socially approved directions.

Hence, as an adult, their own fear and self-hatred are unconscious to the individual precisely because they were never allowed to feel and express them safely as a child. What they do feel, consciously, is their hatred for ‘legitimized’ victims.

Historically, different social groups in different cultural contexts have been the victim of this projected but ‘socially approved’ fear and hatred. Women, indigenous peoples, Catholics, Afro-Americans, Jews, communists, Palestinians…. The list goes on. The predominant group in this category, of course, is children (whose ‘uncontrollability’ frightens virtually all parents until they have been successfully terrorized and tamed).

The groups that are socially approved to be feared and hated are determined by elites. This is because individual members of the elite are themselves terrified and full of self-hatred and they use the various powerful instruments at their disposal – ranging from control of politicians to the corporate media – to trigger the fear and self-hatred of the population at large in order to focus this fear and hatred on what frightens the elite. This makes it easier for the elite to then attack the group that they are projecting frightens them, which is why Donald Trump and various European leaders encourage racist attacks. See, for example, ‘This expert on political violence thinks Trump is making neo-Nazi attacks more likely’. It is also useful for providing a basis for enhancing elite social control through such measures as legislative restrictions on human rights and expanded police powers.

Historically speaking, indigenous peoples and people of color have been primary targets for this projected fear and self-hatred, which explains the psychological origins (which underpin and complement the political and economic origins) of practices such as the Atlantic slave trade and European colonialism in earlier centuries. Racism allows elites and others to project their fear and self-hatred onto indigenous people and people of color so that elites can then seek to destroy this fear and self-hatred.

Obviously, this cannot work. You cannot destroy fear, whether your own or that of anyone else. However, you can cause phenomenal damage to those onto whom your fear and self-hatred are projected. Of course, there is nothing intelligent about this process. If every indigenous person and person of colour in the world was killed, elites would simply then project their fear and self-hatred onto other groups and set out to destroy those groups too.

In fact, of course, western elites are now (unconsciously) projecting their fear and self-hatred onto Muslims as well and this manifests behaviourally in many ways, including as war on countries in the Middle East. And when the blowback from these wars manifests as ‘terrorist’ attacks on western countries (assuming they aren’t ‘false flag’ events, which is often the case), such as the recent attack in Barcelona, it is simply used by elites, employing their corporate media particularly, to justify more intrusive social control under the guise of ‘enhanced security’, as mentioned above.

If you are starting to wonder about the sanity of all this, you can rest assured there is none. Elites are insane. See ‘The Global Elite is Insane’. Unfortunately, the individuals who are mobilized in response to this projection are also insane, as a cursory perusal of their written words and even modest attention to their spoken words will readily illustrate. See, for example, ‘Charlottesville: Race and Terror’.

So is there anything we can do? Fundamentally, we need to stop terrorizing our children. As a back up, we can provide safe spaces for children and adults alike to feel their fear, self-hatred and other suppressed feelings consciously (which will allow them to be safely released). By doing this, we can avoid creating more insane individuals who will project their fear and self-hatred in elite-approved directions. See ‘My Promise to Children’.

If you are fearless enough to recognize that elites are manipulating you into fearing those of other races (or religions) whom we do not need to fear, any time is a good time to speak up and to demonstrate your solidarity. You might also like to sign the online pledge of ‘The People’s Charter to Create a Nonviolent World’.

You are also welcome to consider using the strategic framework explained in Nonviolent Campaign Strategy for your anti-racism campaign. And if you want to organise a nonviolent action to combat racism in a context where violence might erupt, you can minimize the risk of this violence by following the comprehehensive list of guidelines here: ‘Nonviolent Action: Minimizing the Risk of Violent Repression’.

Suppressed fear and self-hatred must be projected and they are usually projected in socially approved ways (although mental illnesses and some forms of criminal activity are ways in which this suppressed fear manifests that are not socially approved).

In essence, racism is a manifestation of the mental illness of elites manipulating us into doing their insane bidding. Unfortunately, many people are easy victims of this manipulation because they are full of suppressed terror and self-hatred too.

Robert J. Burrowes has a lifetime commitment to understanding and ending human violence. He has done extensive research since 1966 in an effort to understand why human beings are violent and has been a nonviolent activist since 1981. He is the author of ‘Why Violence?’ His email address is flametree@riseup.net and his website is here.

Nonviolent Action: Why and How it Works

Nonviolent Action: Why and How it Works

Nonviolent action is extremely powerful.

Unfortunately, however, activists do not always understand why nonviolence is so powerful and they design ‘direct actions’ that are virtually powerless.

I would like to start by posing two questions. Why is nonviolent action so powerful? And why is using it strategically so transformative?

When an activist group is working on an issue – such as a national liberation struggle, war, the climate catastrophe, violence against women and/or children, nuclear weapons, drone killings, rainforest destruction, encroachments on indigenous land – they will often plan an action that is intended to physically halt an activity, such as the activities of a military base, the loading of a coal ship, the work of a bulldozer, the building of an oil pipeline. Their plan might also include using one or more of a variety of techniques such as locking themselves to a piece of equipment (‘locking-on’) to prevent it from being used. Separately or in addition, they might use secrecy both in their planning and execution so that they are able to carry out the action before police or military personnel prevent them from doing so.

Unfortunately, the focus on physical outcomes (including actions such as ‘locking-on’ and its many equivalents), and the secrecy necessary to carry out their plan, all functionally undermine the power of their action. Why is this? Let me explain how and why nonviolent action works so that it is clear why any nonviolent activist who understands the dynamics of nonviolent action is unconcerned about the immediate physical outcome of their action (and what is necessary to achieve that).

If you think of your nonviolent action as a physical act, then you will tend to focus your attention on securing a physical outcome from your planned action: to prevent the military from occupying a location, to stop a bulldozer from knocking down trees, to halt the work at an oil terminal or nuclear power station, to prevent construction equipment being moved on site. Of course, it is simple enough to plan a nonviolent action that will do any of these things for a period of time and there are many possible actions that might achieve it.

But if you pause to consider how your nonviolent action might have psychological and political impact that leads to lasting or even permanent change on the issue in question but also society as a whole, then your conception of what you might do will be both expanded and deepened. And you will be starting to think strategically about what it means to mobilise large numbers of people to think and behave differently.

After all, whatever the immediate focus of your action, it is only ever one step in the direction of more profound change. And this profound change must include a lasting change in prevailing ideas and a lasting change in ‘normal’ behaviour by substantial (and perhaps even vast) numbers of people. Or you will be back tomorrow, the day after and so on until you get tired of doing something without result, as routinely happens in campaigns that ‘go nowhere’ (as so many do).

So why does nonviolent action work?

Fundamentally, nonviolent action works because of its capacity to create a favourable political atmosphere (because of, for example, the way in which activist honesty builds trust), its capacity to create a non-threatening physical environment (because of the nonviolent discipline of the activists), and its capacity to alter the human psychological conditions (both innate and learned) that make people resist new ideas in the first place. This includes its capacity to reduce or eliminate fear and its capacity to ‘humanise’ activists in the eyes of more conservative sections of the community. In essence, nonviolent activists precipitate change because people are inspired by the honesty, discipline, integrity, courage and determination of the activists – despite arrests, beatings or imprisonment – and are thus inclined to identify with them. Moreover, as an extension of this, they are inclined to change their behaviour to act in solidarity.

It is for this reason too that a nonviolent action should always make explicit what behavioural change it is asking of people. Whether communicated in news conferences or via the various media, painted on banners or in other ways, a nonviolent action group should clearly communicate powerful actions that individuals can take. For example, a climate action group should consistently convey the messages to ‘Save the Climate: Become a Vegan/Vegetarian’, ‘Save the Climate: Boycott Cars’ and, like a rainforest action group, ‘Don’t Buy Rainforest Timber’.

A peace group should consistently convey such messages as ‘Don’t Pay Taxes for War’ and ‘Divest from the Weapons Industry’ (among many other possibilities). Groups resisting the nuclear fuel cycle and fossil fuel industry in their many manifestations should consistently convey brief messages that encourage reduced consumption and a shift to more self-reliant renewable energies. See, for example, ‘The Flame Tree Project to Save Life on Earth’.

Groups struggling to defend or reinstate indigenous sovereignty should convey compelling messages that explain what people can do in their particular context.

It is important that these messages require powerful personal action, not token responses. And it is important that these actions should not be directed at elites or lobbying elites. Elites will fall into line when we have mobilized enough people so that they are compelled to do as we wish. And not before. At the end of the Salt March in 1930 Gandhi picked up a handful of salt on the beach at Dandi. This was the signal for Indians everywhere to start collecting their own salt in violation of British law. In subsequent campaigns Gandhi called for Indians to boycott British cloth and make their own khadi (handwoven cloth). These actions were strategically focused because they undermined the profitability of British colonialism in India and nurtured Indian self-reliance.

It is important that these messages require powerful personal action, not token responses. And it is important that these actions should not be directed at elites or lobbying elites. Elites will fall into line when we have mobilized enough people so that they are compelled to do as we wish. And not before. At the end of the Salt March in 1930 Gandhi picked up a handful of salt on the beach at Dandi. This was the signal for Indians everywhere to start collecting their own salt in violation of British law. In subsequent campaigns Gandhi called for Indians to boycott British cloth and make their own khadi (handwoven cloth). These actions were strategically focused because they undermined the profitability of British colonialism in India and nurtured Indian self-reliance.

A key reason why Mohandas K. Gandhi was that rarest of combinations – a master nonviolent strategist and a master nonviolent tactician – was because he understood the psychology of nonviolence and how to make it have political impact. Let me illustrate this point by using the nonviolent raid on the Dharasana salt works, the nonviolent action he planned as a sequel to the more famous Salt March in 1930.

On 4 May 1930 Gandhi wrote to Lord Irwin, Viceroy of India, advising his intention to lead a party of nonviolent activists to raid the Dharasana Salt Works to collect salt and thus intervene against the law prohibiting Indians from collecting their own salt. Gandhi was immediately arrested, as were many other prominent nationalist leaders such as Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel.

Nevertheless, having planned for this contingency, under a succession of leaders (who were also progressively arrested) the raid went ahead as planned with hundreds of Indian satyagrahis (nonviolent activists) attempting to nonviolently invade the salt works. However, despite repeated attempts by these activists to walk into the salt works during a three week period, not one activist got a pinch of salt! Moreover, hundreds of satyagrahis were injured, many receiving fractured skulls or shoulders, and two were killed.

But an account of the activists’ nonviolent discipline, commitment and courage – under the steel-tipped lathi (baton) blows of the police – was reported in 1,350 newspapers around the world. As a result, this nonviolent action – which ‘failed’ to achieve the stated physical objective of seizing salt – functionally undermined support for British imperialism in India. For an account of the salt raids at Dharasana, see Thomas Weber. ‘“The Marchers Simply Walked Forward Until Struck Down”: Nonviolent Suffering and Conversion’

If the activists had been preoccupied with the physical seizure of salt and, perhaps, resorted to the use of secrecy to get it, there would have been no chance to demonstrate their honesty, integrity, courage and determination – and to thus inspire empathy for their cause – although they might have got some salt! (Of course, if salt had been removed secretly, the British government could, if they had chosen, ignored it: after all, who would have known or cared? However, they could not afford to let the satyagrahis take salt openly because salt removal was illegal and failure to react would have shown the salt law – a law that represented the antithesis of Indian independence – to be ineffective.)

In summary, nonviolent activists who think strategically understand that strategic effectiveness is unrelated to whether or not the action is physically successful (provided it is strategically selected, well-designed so that it elicits one or other of the intended responses, and sincerely attempted). Psychological, and hence political, impact is gained by demonstrating qualities that inspire others and move them to act personally too. For this reason, among several others, secrecy (and the fear that drives it) is counterproductive if strategic impact is your intention.

If you are interested in planning effective nonviolent actions, a related article also explains the vital distinction between ‘The Political Objective and Strategic Goal of Nonviolent Actions’.

And if you are concerned about violent military or police responses, have a look at ‘Nonviolent Action: Minimizing the Risk of Violent Repression’.

For those of you who are interested in planning and acting strategically in your nonviolent struggle, whatever its focus, you might be interested in one or the other of these two websites: Nonviolent Campaign Strategy

and Nonviolent Defense/Liberation Strategy.

And if you are interested in being part of the worldwide movement to end all violence, you are welcome to sign the online pledge of ‘The People’s Charter to Create a Nonviolent World’.

Struggles for peace, justice, sustainability and liberation often fail. Almost invariably, this is due to the failure to understand the psychology, politics and strategy of nonviolence. It is not complicated but it requires a little time to learn.

Robert J. Burrowes has a lifetime commitment to understanding and ending human violence. He has done extensive research since 1966 in an effort to understand why human beings are violent and has been a nonviolent activist since 1981. He is the author of ‘Why Violence?’ http://tinyurl.com/whyviolence His email address is flametree@riseup.net and his website is here. http://robertjburrowes.wordpress.com

The original source of this article is Global Research

Sunday, October 29, 2017

A Nonviolent Strategy to Defeat Genocide

A Nonviolent Strategy to Defeat Genocide

It is a tragic measure of the depravity of human existence that genocide is a continuing and prevalent manifestation of violence in the international system, despite the effort following World War II to abolish it through negotiation, and then adoption and ratification of the 1948 Genocide Convention.

According to the Genocide Convention, genocide is any act committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group by killing members of the group, causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group, deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part, imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group and/or forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

While this definition is contested because, for example, it excludes killing of political groups, and words such as ‘democide’ (the murder or intentionally reckless and depraved disregard for the life of any person or people by their government,) and ‘politicide’ (the murder of any person or people because of their political or ideological beliefs) have been suggested as complementary terms, in fact atrocities that have been characterized as ‘genocide’ by various authors include mass killings, mass deportations, politicides, democides, withholding of food and/or other necessities of life, death by deliberate exposure to invasive infectious disease agents or combinations of these. See ‘Genocides in history’.

While genocide and attempts at genocide were prevalent enough both before World War II (just ask the world’s indigenous peoples) and then during World War II itself, which is why the issue attracted serious international attention in the war’s aftermath, it cannot be claimed that the outlawing of genocide did much to end the practice, as the record clearly demonstrates.

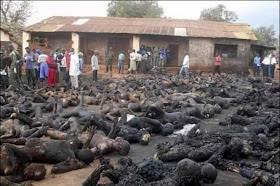

A Rwandan boy covers his face from the stench of dead bodies in this July 19, 1994 file photo. (Source: About Rwanda)

Moreover, given that the United Nations and national governments, out of supposed ‘deference’ to ‘state sovereignty’, have been notoriously unwilling and slow to meaningfully respond to genocides, as was the case in Rwanda in 1994 and has been the case with the Rohingya in Myanmar (Burma) for four decades – as carefully documented in ‘The Slow-Burning Genocide of Myanmar’s Rohingya’ – there is little evidence to suggest that major actors in the international system have any significant commitment to ending the practice, either in individual cases or in general. For example, as official bodies of the world watch, solicit reports and debate whether or not the Rohingya are actually victims of genocide, this minority Muslim population clearly suffers from what many organizations and any decent human being have long labeled as such. For a sample of the vast literature on this subject, see ‘The 8 Stages of Genocide Against Burma’s Rohingya’ and ‘Countdown to Annihilation: Genocide in Myanmar’.

Burma’s Rohingya genocide (Source: The Cutting Edge)

Of course, it is not difficult to understand institutional inaction. Despite its fine rhetoric and even legal provisions, the United Nations, acting in response to the political and corporate elites that control it, routinely fails to act to prevent or halt wars (despite a UN Charter and treaties, such as the Kellogg-Briand Pact, that empower and require it to do so), routinely fails to defend refugees, routinely fails to act decisively on issues (such as nuclear weapons and the climate catastrophe) that constitute global imperatives for human survival, and turns the other way when peoples under military occupation (such as those of Tibet, West Papua, Western Sahara and Palestine) seek their support.

Why then should those under genocidal assault expect supportive action from the UN or international community in general? The factors which drive these manifestations of violence serve a diverse range of geopolitical interests in each case, and are usually highly profitable into the bargain. What hope justice or even decency in such circumstances?

Moreover, the deep psychological imperatives that drive the phenomenal violence in the international system are readily nominated: in essence, phenomenal fear, self-hatred and powerlessness. These psychological characteristics, together with the others that drive the behaviour of perpetrators of violence, have been identified and explained – see ‘Why Violence?’ and ‘Fearless Psychology and Fearful Psychology: Principles and Practice’– but it is the way these (unconsciously and deeply-suppressed) emotions are projected that is critical to understanding the violent (and insane) behavioural outcomes in our world. For brief explanations see, for example, ‘Understanding Self-Hatred in World Affairs’ and ‘The Global Elite is Insane’.

Given the deep psychological imperatives that drive the violence of global geopolitics and corporate exploitation (as well as national, subnational and individual acts of violence), we cannot expect a compassionate and effective institutional response to genocide in the prevailing institutional order, as the record demonstrates. So, is there anything a targeted population can do to resist a genocidal assault?

Fortunately, there is a great deal that a targeted population can do. The most effective response is to develop and implement a comprehensive nonviolent strategy to either prevent a genocidal assault in the first place or to halt it once it has begun. This is done most effectively by using a sound strategic framework that guides the comprehensive planning of the strategy. Obviously, there is no point designing a strategy that is incomplete or cannot be successful.

A sound strategic framework enables us to think and plan strategically so that once our strategy has been elaborated, it can be widely shared and clearly understood by everyone involved. It also means that nonviolent actions can then be implemented because they are known to have strategic utility and that precise utility is understood in advance. There is little point taking action at random, especially if our opponent is powerful and committed (even if that ‘commitment’ is insane which, as briefly noted above, is invariably the case).

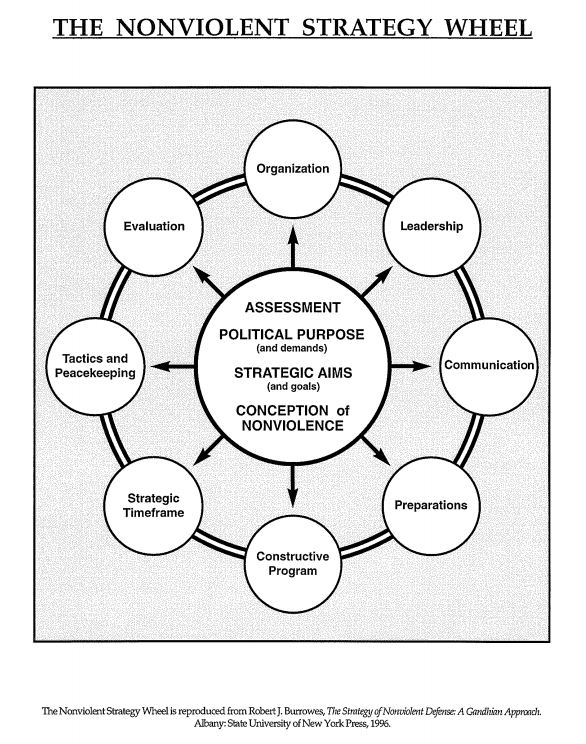

There is a simple diagram presenting a 12-point strategic framework illustrated here in the form of the ‘Nonviolent Strategy Wheel’.

In order to think strategically about nonviolently defending against a genocidal assault, a clearly defined political purpose is needed; that is, a simple summary statement of ‘what you want’. In general terms, this might be stated thus: To defend the [nominated group] against the genocidal assault and establish the conditions for the group to live in peace, free of violence and exploitation.

Once the political purpose has been defined, the two strategic aims (‘how you get what you want’) of the strategy acquire their meaning. These two strategic aims (which are always the same whatever the political purpose) are as follows:

1. To increase support for the struggle to defeat the genocidal assault by developing a network of groups who can assist you.2. To alter the will and undermine the power of those groups inciting, facilitating, organizing and conducting the genocide.

While the two strategic aims are always the same, they are achieved via a series of intermediate strategic goals which are always specific to each struggle. I have identified a generalized set of 48 strategic goals that would be appropriate in the context of ending any genocide here. These strategic goals can be readily modified to the circumstances of each particular instance of genocide.

Many of these strategic goals would usually be tackled by action groups working in solidarity with the affected population campaigning in third-party countries. Of course, individual activist groups would usually accept responsibility for focusing their work on achieving just one or a few of the strategic goals (which is why any single campaign within the overall strategy is readily manageable).

As I hope is apparent, the two strategic aims are achieved via a series of intermediate strategic goals.

Not all of the strategic goals will need to be achieved for the strategy to be successful but each goal is focused in such a way that its achievement will functionally undermine the power of those conducting the genocide.

It is the responsibility of the struggle’s strategic leadership to ensure that each of the strategic goals, which should be identified and prioritized according to their precise understanding of the circumstances in the country where the genocide is occurring, is being addressed (or to prioritize if resource limitations require this).

I wish to emphasize that I have only briefly discussed two aspects of a comprehensive strategy for ending a genocide: its political purpose and its two strategic aims (with its many subsidiary strategic goals). For the strategy to be effective, all twelve components of the strategy should be planned (and then implemented). See Nonviolent Defense/Liberation Strategy.

This will require, for example, that tactics that will achieve the strategic goals must be carefully chosen and implemented bearing in mind the vital distinction between the political objective and strategic goal of any such tactic. See ‘The Political Objective and Strategic Goal of Nonviolent Actions’.

It is not difficult to nonviolently defend a targeted population against genocide. Vitally, however, it requires a leadership that can develop a sound strategy so that people are mobilized and deployed effectively.

Robert J. Burrowes has a lifetime commitment to understanding and ending human violence. He has done extensive research since 1966 in an effort to understand why human beings are violent and has been a nonviolent activist since 1981. He is the author of ‘Why Violence?’. His email address is flametree@riseup.net and his website is here.

Featured image: Genocide Watch

A Nonviolent Strategy to End Violence and Avert Human Extinction.

A Nonviolent Strategy to End Violence and Avert Human Extinction. The Teachings of Gandhi and Martin Luther King

Around the world activists who are strategic thinkers face a daunting challenge to effectively tackle the multitude of violent conflicts, including the threat of human extinction, confronting human society in the early 21st century.

Around the world activists who are strategic thinkers face a daunting challenge to effectively tackle the multitude of violent conflicts, including the threat of human extinction, confronting human society in the early 21st century.

I wrote that ‘activists who are strategic thinkers face a daunting challenge’ because there is no point deluding ourselves that the insane global elite – see ‘The Global Elite is Insane’ – with its compliant international organizations (such as the UN) and national governments following orders as directed, is going to respond appropriately and powerfully to the multifaceted crisis that it has been progressively generating since long before the industrial revolution.

For reasons that are readily explained psychologically – see ‘Love Denied: The Psychology of Materialism, Violence and War’and, for more detail, see ‘Why Violence?’ and ‘Fearless Psychology and Fearful Psychology: Principles and Practice’– this insanity focuses their attention on securing control of the world’s remaining resources while marginalizing the bulk of the human population in ghettos, or just killing them outright with military violence or economic exploitation (or the climate/ecological consequences of their violence and exploitation).

If you doubt what I have written above, then consider the history of any progressive political, social, economic and environmental change in the past few centuries and you will find a long record of activist planning, organizing and action preceding any worthwhile change which was invariably required to overcome enormous elite opposition. In short, if you can identify one progressive outcome that was initiated and supported by the global elite, I would be surprised to hear about it.

Moreover, we are not going to get out of this crisis – which must include ending violence, exploitation and war, halting the destruction of Earth’s biosphere and ongoing violent assaults on indigenous peoples, ending slavery, liberating occupied countries such as Palestine, Tibet and West Papua, removing dictatorships such as those in Cambodia and Saudi Arabia, ending genocidal assaults such as those currently being directed against the people of Yemen and the Rohingya in Myanmar, and defending the rights of a people, such as those in Catalonia, to secede from one state and form another – without both understanding the deep drivers of conflict as well as the local drivers in each case, and then developing and implementing sound and comprehensive strategies, based on this dual-faceted analysis of each conflict.

In addition, if like Mohandas K. Gandhi, many others and me you accept the evidence that violence is inherently counterproductive and has no countervailing desirability in any context – expressed most simply by the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. when he stated ‘the enemy is violence’ – then we must be intelligent, courageous and resourceful enough to commit ourselves to planning, developing and implementing strategies that are both exclusively nonviolent and powerfully effective against extraordinarily insane and ruthlessly violent opponents, such as the US government.

Equally importantly, however, it is not just the violence of the global elite that we must address if extinction is to be averted. We must also tackle the violence that each of us inflicts on ourselves, our children, each other and the Earth too. And, sadly, this violence takes an extraordinary variety of forms having originated no later than the Neolithic Revolution 12,000 years ago. See ‘A Critique of Human Society since the Neolithic Revolution’.

Is all of this possible?

When I first became interested in nonviolent strategy in the early 1980s, I read widely. I particularly sought out the literature on nonviolence but, as my interest deepened and I tried to apply what I was reading in the nonviolence literature to the many nonviolent action campaigns in which I was involved, I kept noticing how inadequate these so-called ‘strategies’ in the literature actually were, largely because they did not explain precisely what to do, even though they superficially purported to do so by offering ‘principles’, ‘guidelines’, sets of tactics or even ‘stages of a campaign’.

I found this shortcoming in the literature most instructive and, because I am committed to succeeding when I engage as a nonviolent activist, I started to read the work of Mohandas K. Gandhi and even the literature on military strategy. By the mid-1980s I had decided to research and write a book on nonviolent strategy because, by then, I had become aware that the individual who understood strategy, whether nonviolent or military, was rare.

Moreover, there were many conceptions of military strategy, written over more than 2,000 years, and an increasing number of conceptions of what was presented as ‘nonviolent strategy’, in one form or another, were becoming available as the 1980s progressed. But the flaws in these were increasingly and readily apparent to me as I considered their inadequate theoretical foundations or tried to apply them in nonviolent action campaigns.

The more I struggled with this problem, the more I found myself reading ‘The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi’ in a library basement. After all, Gandhi had led a successful 30 year nonviolent liberation struggle to end the British occupation of India so it made sense that he had considerable insight regarding strategy. Unfortunately, he never wrote it down simply in one place.

A complicating but related problem was that among those military authors who professed to present some version of ‘strategic theory’, in fact, most simply presented an approach to strategic planning (such as using a set of principles or a particular operational pattern) or an incomplete theory of strategy (such as ‘maritime theory’, ‘air theory’ or ‘guerrilla theory’) and (often largely unwittingly) passed these off as ‘strategic theory’, which they are not. And it was only when I read Carl von Clausewitz’s infuriatingly convoluted and tortuously lengthy book On War that I started to fully understand strategic theory. This is because Clausewitz actually presented (not in a simple form, I hasten to admit) a strategic theory and then a military strategy that worked in accordance with his strategic theory. ‘Could this strategic theory work in guiding a nonviolent strategy?’ I wondered.

Remarkably, the more I read Gandhi (and compared him with other activists and scholars in the field), the more it became apparent to me that Gandhi was the only nonviolent strategist who (intuitively) understood strategic theory. Although, to be fair, it was an incredibly rare military strategist who understood strategic theory either with Mao Zedong a standout exception and other Marxist strategists like Vladimir Lenin and Võ Nguyên Giáp understanding far more than western military strategists which is why, for example, the US and its allies were defeated in their war on Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.

Some years later, after grappling at length with this problem of using strategic theory to guide nonviolent strategy and reading a great deal more of Gandhi, while studying many nonviolent struggles and participating in many nonviolent campaigns myself, I wrote The Strategy of Nonviolent Defense: A Gandhian Approach. I wrote this book by synthesizing the work of Gandhi with some modified insights of Clausewitz and learning of my own drawn from the experience and study just mentioned. I have recently simplified and summarized the presentation of this book on two websites: Nonviolent Campaign Strategy and Nonviolent Defense/Liberation Strategy.

Let me outline, very simply, nonviolent strategy, without touching on strategic theory, as I have developed and presented it in the book and on the websites.

Nonviolent Strategy

You will see on the diagram of the Nonviolent Strategy Wheel that there are four primary components of strategy in the center of the wheel and eight components of strategy that are planned in accordance with these four central components. I will briefly describe the four primary components.

Source: Nonviolent Campaign Strategy

Before doing so, however, it is worth noting that, by using this Nonviolent Strategy Wheel, it is a straightforward task to analyze why so many activist movements and (nonviolent) liberation struggles fail: they simply do not understand the need to plan and implement a comprehensive strategy, entailing all twelve components, if they are to succeed.

So, to choose some examples almost at random, despite substantial (and sometimes widespread) popular support, particularly in some countries, the antiwar movement, the climate justice movement and the Palestinian and Tibetan liberation struggles are each devoid of a comprehensive strategy to deploy their resources for strategic impact and so they languish instead of precipitating the outcomes to which they aspire, which are quite possible.

Having said that a sound and comprehensive strategy must pay attention to all twelve components of strategy it is very occasionally true that campaigns succeed without doing so. This simply demonstrates that nonviolence, in itself, is extraordinarily powerful. But it is unwise to rely on the power of nonviolence alone, without planning and implementing a comprehensive strategy, especially when you are taking on a powerful and entrenched opponent who has much to lose (even if their conception of what they believe they will ‘lose’ is delusional) and may be ruthlessly violent if challenged.

For the purpose of this article, the term strategy refers to a planned series of actions (including campaigns) that are designed to achieve the two strategic aims (see below).

The Political Purpose and the Political Demands

If you are going to conduct a nonviolent struggle, whether to achieve a peace, environmental or social justice outcome, or even a defense or liberation outcome, the best place to start is to define the political purpose of your struggle. The political purpose is a statement of ‘what you want’. For example, this might be one of the following (but there are many possibilities depending on the context):

- To secure a treaty acknowledging indigenous sovereignty between [name of indigenous people] and the settler population in [name of land/country] over the area known as [name of land/country].

- To stop violence against [children and/or women] in [name of the town/city/state/country].

- To end discrimination and violence against the racial/religious minority of [name of group] in [name of the town/city/state/country].

- To end forest destruction in [your specified area/country/region].

- To end climate-destroying activities in [name of the town/city/state/country].

- To halt military production by [name of weapons corporation]in [name of the town/city/state/country].

- To prevent/halt [name of corporation] exploiting the [name of fossil fuel resource].

- To defend [name of the country] against the political/military coup by [identity of coup perpetrators].

- To defend [name of the country] against the foreign military invasion by [name of invading country].

- To defend the [name of targeted group] against the genocidal assault by the [identity of genocidal entity].

- To establish the independent entity/state of [name of proposed entity/state] by removing the foreign occupying state of [name of occupying state].

- To establish a democratic state in [name of country] by removing the dictatorship.

This political purpose ‘anchors’ your campaign: it tells people what you are concerned about so that you can clearly identify allies, opponents and third parties. Your political purpose is a statement of what you will have achieved when you have successfully completed your strategy.

In practice, your political purpose may be publicized in the form of a political program or as a list of demands. You can read the five criteria that should guide the formulation of these political demands on one of the nonviolent strategy websites cited above.

The Political and Strategic Assessment

Strategic planning requires an accurate and thorough political and strategic assessment (although ongoing evaluation will enable refinement of this assessment if new information emerges during the implementation of the strategy).

In essence, this political and strategic assessment requires four things. Notably this includes knowledge of the vital details about the issue (e.g. why has it happened? who benefits from it? how, precisely, do they benefit? who is exploited?) and a structural analysis and understanding of the causes behind it, including an awareness of the deep emotional (especially the fear) and cultural imperatives that exist in the minds of those individuals (and their organizations) who engage in the destructive behavior.

So, for example, if you do not understand, precisely, what each of your various groups of opponents is scared of losing/suffering (whether or not this fear is rational), you cannot design your strategy taking this vital knowledge into account so that you can mitigate their fear effectively and free their mind to thoughtfully consider alternatives. It is poor strategy (and contrary to the essence of Gandhian nonviolence) to reinforce your opponents’ fear and lock them into a defensive reaction.

Strategic Aims and Strategic Goals

Having defined your political purpose, it is easy to identify the two strategic aims of your struggle. This is because every campaign or liberation struggle has two strategic aims and they are always the same:

- To increase support for your campaign by developing a network of groups who can assist you.

- To alter the will and undermine the power of those groups who support the problem.

Now you just need to define your strategic goals for both mobilizing support for your campaign and for undermining support for the problem. From your political and strategic assessment:

- Identify the key social groups that can be mobilized to support and participate in your strategy (and then write these groups into the ‘bubbles’ on the left side of the campaign strategy diagram that can be downloaded from the strategy websites), and

- identify the key social groups (corporation/s, police/military, government, workers, consumers etc.) whose support for the problem (e.g. the climate catastrophe, war, the discrimination/violence against a particular group, forest destruction, resource extraction, genocide, occupation) is vital (and then write these groups into the columns on the right side of the campaign strategy diagram).

These key social groups become the primary targets in your campaign. Hence, the derivative set of specific strategic goals, which are unique to your campaign, should then be devised and each written in accordance with the formula explained in the article ‘The Political Objective and Strategic Goal of Nonviolent Actions’. That is: ‘To cause a [specified group of people] to act in the [specified way].’

As the title of this article suggests, it also explains the vital distinction between the political objective and the strategic goal of any nonviolent action. This distinction is rarely understood and applied and explains why most ‘direct actions’ have no strategic impact.

You can read appropriate sets of strategic goals for ending war, ending the climate catastrophe, ending a military occupation, removing a dictatorship and halting a genocide on one or the other of these two sites: Nonviolent Campaign Strategic Aims and Nonviolent Defense/Liberation Strategic Aims.

The Conception of Nonviolence

There are four primary conceptions of nonviolence which have been illustrated on the Matrix of Nonviolence. Because of this, your strategic plan should:

- identify the particular conception of nonviolence that your campaign will utilize;

- identify the specific ways in which your commitment to nonviolence will be conveyed to all parties so that the benefits of adopting a nonviolent strategy are maximized; and

- identify how the level of discipline required to implement your nonviolent strategy will be developed. This includes defining the ‘action agreements’ (code of nonviolent discipline) that will guide activist behaviour.

It is important to make a deliberate strategic choice regarding the conception of nonviolence that will underpin your strategy. If your intention is to utilize the strategic framework outlined here, it is vitally important to recognize that this framework is based on the Gandhian (principled/revolutionary) conception of nonviolence.

This is because Gandhi’s nonviolence is based on certain premises, including the importance of the truth, the sanctity and unity of all life, and the unity of means and end, so his strategy is always conducted within the framework of his desired political, social, economic and ecological vision for society as a whole and not limited to the purpose of any immediate campaign. It is for this reason that Gandhi’s approach to strategy is so important. He is always taking into account the ultimate end of all nonviolent struggle – a just, peaceful and ecologically sustainable society of self-realized human beings – not just the outcome of this campaign. He wants each campaign to contribute to the ultimate aim, not undermine vital elements of the long-term and overarching struggle to create a world without violence.

This does not mean, however, that each person participating in the strategy must share this commitment; they may participate simply because it is expedient for them to do so. This is not a problem as long as they are willing to commit to the ‘code of nonviolent discipline’ while participating in the campaign.

Hopefully, however, their participation on this basis will nurture their own personal journey to embrace the sanctity and unity of all life so that, subsequently, they can more fully participate in the co-creation of a nonviolent world.

Other Components of Strategy

Once you have identified the political purpose, strategic aims and conception of nonviolence that will guide your struggle, and undertaken a thorough political and strategic assessment, you are free to consider the other components of your strategy: organization, leadership, communication, preparations, constructive program, strategic timeframe, tactics and peacekeeping, and evaluation.

For example, a vital component of any constructive program ideally includes each individual traveling their own personal journey to self-realization – see ‘Putting Feelings First’– considering making ‘My Promise to Children’ to eliminate violence at its source and participating in ‘The Flame Tree Project to Save Life on Earth’ to preserve Earth’s biosphere.

Needless to say, each of these components of strategy must also be carefully planned. They are explained in turn on the nonviolent strategy websites mentioned above.

In addition to these components, the websites also include articles, photos, videos, diagrams and case studies that discuss and illustrate many essential elements of sound nonviolent strategy. These include the value of police/military liaison, issues in relation to tactical selection, the importance of avoiding secrecy and sabotage, how to respond to arrest, how to undertake peacekeeping and the 20 points to consider when planning to minimize the risk of violent police/military repression when this is a possibility.

Conclusion

The global elite and many other people are too insane to ‘walk away’ from the enormous violence they inflict on life.

Consequently, we are not going to end violence in all of its forms – including violence against women, children, indigenous and working peoples, violence against people because of their race or religion, war, slavery, the climate catastrophe, rainforest destruction, military occupations, dictatorships and genocides – and create a world of peace, justice and ecological sustainability for all of us without sound and comprehensive nonviolent strategies that tackle each issue at its core while complementing and reinforcing gains made in parallel struggles.

If you wish to declare your participation in this worldwide effort, you are welcome to sign the online pledge of ‘The People’s Charter to Create a Nonviolent World’.

Given the overwhelming violence that we must tackle, can we succeed? I do not know but I intend to fight, strategically, to the last breath. I hope that you will too.

Robert J. Burrowes has a lifetime commitment to understanding and ending human violence. He has done extensive research since 1966 in an effort to understand why human beings are violent and has been a nonviolent activist since 1981. He is the author of ‘Why Violence?’ His email address is flametree@riseup.net and his website is here.

The original source of this article is Global Research